Lets Talk! |

Lets Connect! |

|||||||||||||

| Are you in need of captivating content for your clean technology project? Look no further! Our extensive research capabilities will provide you with the market-related content you're seeking. Discover more about how we can help you today! | +44 7594 649 748 | We're across all the major socials. Find out what we have to say about all things to do with new technology, markets, economics and the policies, that will shape our planet's future. Disagree with us? Let us know | ||||||||||||

| Schedule some time with us |  |

|||||||||||||

| info@supplier-strategies.com | ||||||||||||||

According to a recent review by researchers from China and elsewhere, perovskite solar cells have achieved a record efficiency of 25.6%, surpassing that of many existing solar panels. The review also highlighted the progress of perovskite-based tandem solar cells, which have reached an efficiency of over 29%. Moreover, the review discussed the advances in lead-free perovskites, which aim to address the toxicity issue of lead-based perovskites.

Although market data is scarce, due to its limited usage currently, various market research houses including Precedence Research, and Allied Market Research Astute Analytica all suggest compound annual growth rates of around 35% over the next 10 years, with the global market for perovskite-based solar panels to reach more than $6bn by 2030. Great for solar panel suppliers, and the perovskite supply chain. Not such good news for those communities affected by its extraction and processing.

Perovskite is primarily found in countries such as China, Russia, and the United States. The mining of perovskite can have severe environmental impacts, including water pollution, land degradation, and deforestation. These environmental impacts can also have profound consequences for the communities living near the mining sites.

According to a study by researchers from MIT and elsewhere, the mining of perovskite can cause up to 16 times more greenhouse gas emissions than the mining of silicon, the most widely used material for solar panels. The study also found that the mining of perovskite can consume up to 75 times more water than the mining of silicon, and up to 19 times more land area.

The mining of perovskite can also have negative social impacts on local communities. Mining operations can displace communities, disrupt their traditional way of life, and cause conflicts over land use. Moreover, mining activities often provide limited employment opportunities for local people, and the jobs are often low-paying and dangerous.

According to a report by Amnesty International, the mining of perovskite in China has been linked to human rights violations, such as forced evictions, land grabs, and lack of consultation and compensation. The report also documented cases of child labour, exposure to toxic chemicals, and poor health and safety conditions in perovskite mines.

Furthermore, there are concerns about the working conditions of miners in perovskite mines. Safety standards may not be up to par, and workers may be exposed to harmful chemicals and hazardous working conditions.

Sustainable mining practices and responsible sourcing of perovskite are essential to ensure that mining operations are conducted in an environmentally friendly and socially responsible manner. The industry must work to minimize the environmental impact of mining by implementing measures to reduce pollution, promote reforestation, and protect water sources.

The perovskite industry must also ensure that local communities benefit from mining activities, providing adequate compensation, employment opportunities, and support for local development. This includes working with local communities to understand their needs and concerns and involving them in decision-making processes.

In addition to sustainable mining practices, there is a need for research and development of alternative sources of perovskite. This includes exploring the use of recycled materials and developing new mining techniques that minimize the environmental impact of mining.

Despite the challenges associated with perovskite mining, the potential benefits of the material cannot be ignored. Its high efficiency, versatile applications, and low-cost production make it an attractive alternative to traditional renewable energy devices. With the right approach, perovskite could play a key role in decarbonisation efforts and help us build a sustainable future for generations to come.

Lithium is ubiquitous these days with its increased use in rechargeable batteries found in everything from lorries and cars through to consumer durables and toys. It is found abundantly in many areas of the globe, but in terms of quality its main mining regions are in South America and China. The growth of the EV market is the main driver for the mining and processing of Lithium. Future demand for Lithium is set to dwarf current levels.

Lithium is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal that has many applications in various fields, such as medicine, electronics, energy storage, and aerospace. Lithium is a key material for the transition to a low-carbon economy, as it is used to make lithium-ion batteries that power electric vehicles (EVs) and store renewable energy. However, lithium also poses significant environmental and social challenges, as its extraction and processing require substantial amounts of water, energy, and land, and often affect the livelihoods of local communities and the habitats of wildlife. In this article, we will explore the current and future trends of lithium use, the main lithium sources and deposits, the problems associated with lithium mining, and potential alternatives to lithium batteries.

According to a report by BloombergNEF, global demand for lithium is expected to increase from 47 kilotons (kt) in 2020 to 1,864 kt in 2030, representing a compound annual growth rate of 38%. The main driver of this growth is the EV sector, which accounted for 67% of lithium demand in 2020 and is projected to reach 88% by 2030. The report estimates that there will be 116 million EVs on the road by 2030, up from 10 million in 2020. Other applications of lithium include consumer electronics, grid storage, and industrial uses.

The EV sector is influenced by several factors that affect the demand for lithium, such as battery chemistry, battery size, vehicle range, vehicle efficiency, and vehicle sales. Battery chemistry refers to the composition of the cathode (positive electrode) and the anode (negative electrode) materials in a lithium-ion battery. Different chemistries have different performance characteristics, such as energy density, power density, safety, cost, and lifespan. The most common cathode chemistries are nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC), nickel-cobalt-aluminium (NCA), lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP), and lithium-manganese-oxide (LMO). The most common anode material is graphite.

Battery size refers to the capacity of a battery measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh). Larger batteries can store more energy and provide longer driving range for EVs. However, they also increase the weight and cost of the vehicle. Vehicle range refers to the distance that an EV can travel on a single charge. It depends on factors such as battery size, vehicle efficiency, driving conditions, and driver behaviour. Vehicle efficiency refers to the amount of energy that an EV consumes per unit distance travelled. It depends on factors such as vehicle design, aerodynamics, weight, regenerative braking, and powertrain efficiency. Vehicle sales refer to the number of EVs sold in a given market or region. They depend on factors such as consumer preferences, government policies, infrastructure availability, charging options, and price competitiveness.

The demand for lithium is also influenced by the supply chain dynamics of the lithium industry. Lithium is mainly sourced from two types of deposits: brine and hard rock. Brine deposits are saline water bodies that contain dissolved lithium salts. They are typically found in arid regions such as South America’s Lithium Triangle (Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile), China’s Qinghai province, and Nevada’s Clayton Valley. Hard rock deposits are igneous or metamorphic rocks that contain lithium-bearing minerals such as spodumene or petalite. They are mostly found in Australia, Canada, China, Finland, Portugal, Zimbabwe, and other countries.

The extraction and processing of lithium from these deposits involve different methods and technologies. Brine extraction involves pumping brine from underground reservoirs to evaporation ponds where solar radiation concentrates the lithium salts over several months or years. The concentrated brine is then further purified and converted into lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide using chemical reagents. Hard rock extraction involves mining ore from open-pit or underground mines and crushing it into smaller pieces. The ore is then processed using various techniques such as flotation, roasting involves heating the ore in a furnace with sulphuric acid or sodium carbonate to produce water-soluble lithium sulphate or lithium carbonate. Flotation involves adding chemicals and air bubbles to the ore slurry to separate the lithium-bearing minerals from the waste rock. The separated minerals are then further refined and converted into lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide.

The choice of extraction and processing methods depends on factors such as the grade, quality, and location of the lithium deposit, the availability and cost of water, energy, and chemicals, the environmental and social impacts, and the market demand and price of lithium products. Generally, brine extraction has lower operating costs but higher capital costs than hard rock extraction. Brine extraction also requires more time, water, and land area than hard rock extraction. However, brine extraction can produce higher purity lithium products than hard rock extraction.

Lithium mining poses significant environmental and social challenges for the regions where it takes place. Some of the main problems are:

Water consumption: Lithium extraction and processing consume large amounts of water, especially in arid regions where water is scarce and valuable for human and ecological needs. For example, it is estimated that producing one ton of lithium from brine requires 500,000 gallons of water, which is equivalent to the annual water consumption of 11 people in the US. This can lead to water depletion, contamination, and conflicts with local communities and farmers who depend on water for irrigation, drinking, and sanitation.

Energy consumption: Lithium extraction and processing require large amounts of energy, mostly from fossil fuels, which contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. For example, it is estimated that producing one ton of lithium from brine emits 15 tons of carbon dioxide, which is equivalent to the annual emissions of three cars in the US. This can also increase the dependence on imported oil and gas and create geopolitical risks.

Land degradation: Lithium extraction and processing require large areas of land, which can affect the natural landscape, biodiversity, and ecosystem services. For example, brine extraction involves building evaporation ponds that cover thousands of hectares of land and alter the hydrological cycle, soil quality, and wildlife habitats. Hard rock extraction involves creating open-pit or underground mines that generate waste rock, tailings, dust, noise, and visual impacts. Both methods can also affect the cultural and historical heritage of the land and the indigenous peoples who live there.

In terms of its societal impacts, Lithium and lithium mining is again a mixed bag. On the one hand lithium mining creates jobs, income, infrastructure, and development opportunities for the host countries and regions. Indeed, the European Commission expects the Lithium economy in the EU alone will result in four million new jobs by 2025. McKinsey suggests that producing lithium hydroxide in Australia may create up to 18,000 temporary construction jobs and 4,000 permanent operational jobs by 2030.

On the other hand, lithium mining can also cause displacement, resettlement, human rights violations, health problems, corruption, inequality, and social conflicts among different stakeholders. For example, Salar de Atacama, Chile’s largest salt flat is home to 18 indigenous Atacameño communities. It has been mined extensively for a range of mineral ores much without consultation compensation offered to these indigenous peoples from the mining companies or the government, and their right to prior consent has not been respected. Furthermore. the unequal distribution of benefits and costs from lithium mining has created tensions and protests among the local communities, who demand more participation and transparency in the decision-making process.

Currently, Lithium, or more specifically Lithium-based batteries are our best hope of reaching net-zero. Billions of dollars are being spent on researching alternatives such as hydrogen fuel cells for mass transportation, but the infrastructure, our economies and our laws are geared up for EVs replacing ICEs over the next 5-10 years. Whilst some governments, most notably the UK Government, are back tracking on the timescales, the trajectory looks set. We cannot do nothing, Equally we cannot wait in hope that some technological fix is going to save the day, like the promise of nuclear fusion, seemingly always just a decade away, So despite its limitations, despite the problems it causes, mining lithium is the only game in town right now. What we can do is mine responsibly, fairly and with regard to the people it affects. Will that happen? On this we are not so sure.

In late 2023, years after the decision has been implemented politicians, economists and newspaper columnists of competing persuasions continue to champion or, worse, ignore, the UK’s decision to leave the European Union (EU) in the referendum. At one “coalface” a group of people affected directly by the decision battles almost daily to regain ground up until that June 2016 moment, they thought was secure,

What scientists were promised in the run-up to the referendum was that the UK’s position in the EU innovation funding programme, Horizon, would be protected regardless of the outcome. As with many of the Leave campaigns’ promises however, this was to prove inaccurate.

As a result, although the UK government has half-heartedly flirted with the idea of building its own innovation programme its research community currently finds itself in an invidious position losing vital funding from the EU and finding very little comfort from HMG that the situation will improve any time soon.

However, as we detail below, the damage done to the UK’s innovation infrastructure goes far beyond the material loss of funding. Along with that loss, comes the reputational damage caused to the UK as a magnet for the brightest minds in the world; systematic damage to its universities as hubs for scientific research and innovation; and damage to its proposition for home-grown academics who would otherwise stay and encourage the next of generation of researchers leave the country to find funding elsewhere.

Among all the impacts Brexit has had on the UK economy arguably the felt has been the UK's loss of access to Horizon Europe, the EU's flagship research and innovation program. Its worth spending a few words here to answer the "so what" question. Why is Horizon Europe a big deal for the UK.

Horizon Europe provides a financial lifeline for diverse research projects, spanning from fundamental research to applied innovation. It is in this first category, fundamental research, that the importance of Horizon Europe is most obvious. Fundamental research often referred to as blue skies research is highly speculative. It is painstaking, can be laborious, repetitive and ultimately may produce nothing of any value. This kind of research is unattractive to private companies as its shareholders require returns for their investments. It is let to governments generally to fund this type of research.

And historically the UK has been very good - no - very, very good at attracting research money, because, historically we have been very good at it. In all other regards, such as agricultural subsidies, transport development, regional regeneration programmes, and foreign aid, the UK was by far a net contributor to the EU. However, in science and innovation, through the Horizon Europe programme, the UK secured more than a substantial slice of the funding pie, receiving over €9 billion from the previous Horizon - Horizon 2020 - programme.

To be fair, Boris Johnson’s post-Brexit Government did succeed in gaining associate membership of Horizon Europe, but the relationship has since run into difficulty, primarily because of the Northern Ireland Protocol. The EU suspended the UK’s associate membership of the programme was until it had resolved the issue. However, whilst the Windsor Agreement in March 2023 solved the issue, progress in restoring the UKs associate membership has been slow and only now, 6 months later, does it look to be back on track. The effects of the UKs absence from the programme are stark. European Commission figures suggest a dramatic fall awards to British science programmes in recent years. In 2019 €959.3m (£828.8m) in Horizon 2020 funds grants went 1,364-UK based researchers, compared with €22.18m in 192 grants in 2023 so far. The statistics from the European Commission show that Cambridge University, which was awarded funding of €483m (£433m) over the seven years of the last European research funding programme, Horizon 2020, has not received any funding in the first two years of the current Horizon Europe programme. Meanwhile, Oxford, which won €523m from the earlier programme, has received just €2m to date from Horizon Europe.

The UK's renewed association agreement with the EU means that UK institutions and researchers can apply for funding from Horizon Europe. HMG also states that has secured a new deal which means that it does not need to pay for the period in which it was excluded from the programme and that the UK will have a new automatic clawback that “protects the UK as participation recovers from the effects of the last two and a half years. It means the UK will be compensated should UK scientists receive significantly less money than the UK puts into the programme. This was not the case under the original terms of association.”

Whilst ministers are keen to talk up these financial compensations, there are several issues its less keen to draw attention to. As an associate country to the programme, the UK will be competing with institutions from fifteen other associated countries, including Norway, Israel, and Iceland for funding.

There are fears that even with the UK’s associate membership restored the ability of its institutions to keep their home-grown talent, let alone attract the world’s best talent is irreparably damaged. There is evidence already that some of the UKs best scientists are looking beyond UK institutions to EU-based universities to secure funding. Additionally, some researchers have already reported feeling discouraged from pursuing research in the UK due to the uncertainty caused by Brexit, showing that a brain drain may already be occurring. The University of Oxford experienced a 20% decrease in EU researcher applications in the year following Brexit, a loss it has not recovered. Brexit has also affected the number of EU students enrolling in UK universities. Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) figures show that the number of EU students enrolling for the first year of an undergraduate or postgraduate course was down from 66,680 the year before Brexit came into force, 2020, to 31,000 in 2021, the first year the UK treated EU students as those coming from China or India. This represents a loss of income from international students that is devastating higher education in the UK.

Brexit has significantly inflated the cost of cross-border collaborations for UK researchers. These augmented expenses stem from various sources, including immigration hurdles, visa requirements, and customs clearance. The added financial burden may deter UK researchers from fostering and sustaining international partnerships, ultimately hindering their research pursuits.

Brexit's impact extends to the mobility of scientists and researchers between the UK and the EU. Stringent immigration rules now apply to EU citizens residing in the UK, making it harder for them to work and potentially deterring them from bringing their families along. This impediment could hamper UK universities' efforts to attract and retain talented scientists and researchers from the EU.

Historically, the UK has punched well above its weight in terms of innovation. From the industrial revolution to the discovery of Graphene the UK has attracted and maintained a very high rate of rate of quality innovation. However, the once secure foundations upon which the country has relied to build its reputation are crumbling, despite today’s announcement. The collective consequences of losing access to Horizon Europe: funding, reputational harm, elevated collaboration costs, and reduced researcher mobility have cast a dark shadow over UK innovation that could be terminal.

Let’s not downplay the renewed access to Horizon Europe. Access to the programme is an existential issue for UK innovation and we can only welcome the news and breathe a sigh of relief. But it really is the bare minimum of what needs to be done to resurrect the UK as a world class pace to innovate.

Here is what the UK government needs to do right now to correct the situation.

Far, far, far greater Government funding for blue skies research.

Yes, we’ve heard UK government promises of bolstering research and innovation funding, but sustained and much increased investment is essential. For this there needs to be a strong science lobby leaning on the government at every opportunity to make the case for funding, Ministers, especially those that hold purse strings need to understand the role of science and innovation. We cannot rely on a handful of innovative companies in a small range of science-based industries to invest in blue skies research. Their shareholders will want to see returns for their money. The nature of fundamental scientific research funded by Horizon Europe does not guarantee the returns the shareholders of public companies need to justify the immense costs of this type of research.

Better opportunities for mobility

Streamlining immigration processes for scientists and researchers, both incoming and outgoing, can facilitate international collaborations. Again, the Government have made strides in this. The fast track and lower threshold visa scheme for scientists is helpful, but there needs to be more “pull” for the UK to attract this type of talent.

Investing in Skills and Training

Nurturing UK talent pool through education, skills development, and training programs is pivotal. Its not just about the bright minds who can lead research programmes, identify the right people, and build the right environments for good innovation. It’s the support staff, researchers, support staff, HR, librarians, technicians.

Politicians and newspaper columnists will be at pains to argue that none of the changes to the UK’s higher education landscape and its ability to compete for talent and funding on an international level can be placed solely on the UKs decision to leave the EU. But that is not the point. The facts are that now, in 2023, UK research institutions are not attracting nearly the same amount of talent or funding than it did prior to 2016.

Today’s announcement of the UK’s re-admittance to the Horizon Europe programme will be much vaunted by the Government and its sympathetic press. But it is just a small step which doesn’t even begin to make up for the damage that has already occurred to British innovation.

Copper, an indispensable mineral powering modern technologies such as Li-Ion batteries, electric vehicles, and renewable energy infrastructure, has emerged as a linchpin of progress in the 21st century, just as it did in the second half of the industrial revolution. As the world witnesses a surge in demand for new cleaner, environmentally friendly technologies, the significance of copper in driving technological advancement becomes increasingly apparent. However, beneath its lustrous exterior lies a darker reality – the mining and extraction of copper come at a significant cost, bearing substantial environmental and social impacts.

Copper's exceptional ability to conduct electricity is primarily due to its unique chemical properties. Copper has a low electrical resistivity, which means it offers less resistance to the flow of an electric current. This property allows electrons to move more freely through the material, resulting in efficient electrical conduction. Copper also possesses one of the highest electrical conductivity values among common metals. At room temperature, it has an electrical conductivity of approximately 58.5 million siemens per meter (MS/m). This high conductivity enables the efficient transmission of electric current with minimal energy loss.

Copper's electron configuration also plays a vital role in its electrical conductivity. It has one electron in its outermost shell, which allows it to form a "sea of delocalized electrons" within its crystal lattice. These delocalized electrons can move freely throughout the material, facilitating the flow of electric current. Copper also boasts high thermal conductivity, which means it can efficiently transfer heat. This property is closely related to its electrical conductivity since both involve the movement of electrons and lattice vibrations (phonons).

Copper is a highly ductile and malleable metal, meaning it can be easily drawn into wires and shaped into various forms without losing its conductivity. This property makes it ideal for manufacturing electrical wires and cables. Copper forms a protective oxide layer on its surface, which protects it from corrosion. This oxide layer ensures the longevity and reliability of copper electrical components.

Finally, copper can be alloyed with other metals to enhance specific properties without significantly affecting its excellent electrical conductivity. For example, copper is commonly alloyed with tin to form bronze or with zinc to create brass.

Due to these specific chemical properties, copper has become the material of choice for electrical wiring, power transmission lines, and various electrical components. Its widespread use in electrical applications has significantly contributed to the advancement of modern technology and the efficient distribution of electricity across the globe. It is fair to say that copper, along with iron and steam formed the basis of the industrial revolution in many of the innovations of the age would have been unthinkable without it.

In short copper is valuable.

But like everything upon which we place a value scarcity of supply, endogenous (e.g., the global financial crash of 2008) and exogenous market threats, such as the Covid-19 pandemic mean that the monetary value of copper has undergone significant fluctuations over decades. However, the projected surge in electric vehicle demand is poised to drive up copper prices. As an illustration of the rise in demand for copper indicated by just one technology, the EV the average electric vehicle requires around 83kg of copper, whereas a conventional vehicle demands just over a quarter of this amount.

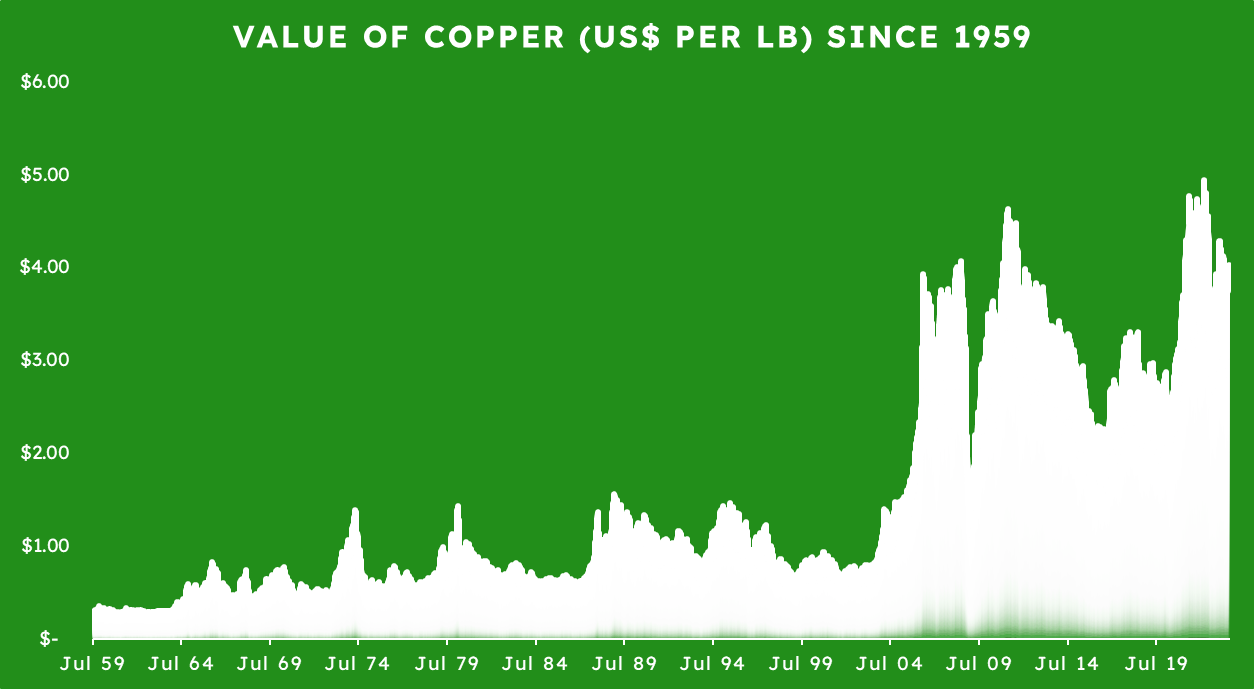

Chart 1: Copper Prices in US$ per lb since 1959 Source: Macrotrends: Copper Prices - 45 Year Historical Chart

Chart 1: Copper Prices in US$ per lb since 1959 Source: Macrotrends: Copper Prices - 45 Year Historical Chart This relentless rise in demand can only mean one thing for the price of copper as Chart 1 illustrates. Indeed, market analysts often refer to copper as the “Doctor” because rising copper prices mean greater demand which means greater economic activity.

In 2021, the world’s copper production was 16,890 thousand tons. The top five producers, responsible for over 75% of global copper ore production, are Peru, China, The Democratic Republic of Congo, and the USA.

However, like any metal ore that needs to be mined, the extraction of copper can have severe environmental and social costs. The process of extracting copper from the Earth brings about far-reaching environmental consequences, leaving an indelible mark on the natural world. The relentless quest for copper necessitates extensive mining operations, involving the removal of overburden and the use of heavy machinery. This process results in soil erosion, as soil particles and pollutants are washed into waterways, leading to contamination and the degradation of fragile ecosystems. Chemicals such as potassium ethyl xanthate (CH3CH2OCS2K) and 4-Methyl-2-pentanol (C6H14O, also known as “MIBC”) are flammable, harmful is swallowed and can cause skin and eye irritant. These chemicals can and have been found in infiltrated water sources, causing water pollution that imperils drinking water safety, jeopardizes fishing industries, and compromises recreational activities.

The 34,000 residents of Butte, Montana live with of the problems copper mining causes to the environment every day, despite the mine closing 40 years ago in 1982. The Berkeley Pit forms part of the Upper Clarke River site, the US’s largest “Superfund" site for environmental clean-up operations.

The copper mining and smelting activity in Butte resulted in significant contamination of an area of land that stretches 120 miles to Milltown, Montana, to the northwest. Sediment flooded out from abandoned mines contaminated with arsenic, copper, zinc. cadmium and lead from mining and smelting copper.

Butte also serves as a reminder that copper mining pursuit of copper necessitates the clearing of vast tracts of land, often leading to the destruction of habitats for countless plant and animal species, consequently contributing to the alarming loss of biodiversity. The former copper mine dominates the landscape. Whilst the pit itself is 1 mile long and ½ a mile wide, the surrounding earthworks cover 8 square miles of poisoned land.

Against this backdrop, the fact that CO2 emissions from copper mining seem almost immaterial. They are not. According to Scarn Associates copper extraction and smelting accounts for “over 86 million tons (Mt CO2e) of Scope 1 and 2 CO2 equivalent emissions, plus an additional 38Mt CO2e associated with freight to importing country port, smelting and refining”.

Beyond the environmental toll, copper mining exacts a heavy human cost, disrupting lives and violating human rights. These include the displacement of local communities, compelling them to abandon their homes, lose ancestral lands, and endure profound disruptions to their livelihoods. The copper mining industry is also responsible for various human rights abuses, including forced labour, child labour, and the use of violence against workers, tarnishing the ethical fabric of copper mining.

In a landmark report released in 2015 Amnesty outlined in detail the abuse of human rights of mineworkers and local inhabitants of mining land in Myanmar. Amongst other allegations Amnesty point out that Canadian mining company Ivanhoe Mines, now Turquoise Hill Resources, knew its investment in the mine would lead to the forcible eviction of thousands of people in the 1990s and that more forcible evictions occurred in 2011for the construction of the Letpadaung mine, run by Chinese company Wanbao and Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings (UMEHL), the economic arm of the Myanmar military, claims that were refuted by Wanbao at the time.

Mitigating the Environmental and Social Impacts of Copper Mining

There is a path to responsible copper mining that necessitates proactive measures and coherent strategies to address the challenges outlined above. These involve the usual elements of money, political will, and resources to manage and monitor both the social and environmental impacts of copper mining and smelting.

Copper is infinitely recyclable. Whilst reclaiming spent copper has its own environmental costs, those costs are far less onerous than those of virgin metal.

Embracing cleaner mining technologies, such as bioleaching, holds the potential to reduce the reliance on harmful chemicals like cyanide, curbing environmental degradation in the process.

Aluminium is often cited as the nearest earth metal replacement for copper. It is lighter, and denser than copper so more wire can be produced per ton than copper. However, this lightness comes at the price of lower conductivity, consequently, more aluminium must be used to pass the same current as copper, which results in larger cables.

More exciting, albeit less of a reality at present, is the possibility that new superconductive materials such as LK-99 could displace coppers pivotal place in multitudes of clean energy applications. The implications of LK-99 or other superconductive materials on existing requirements for copper are significant. If superconductors become commercially viable, the demand for copper would decline significantly.

For example, in power transmission, superconductors could replace copper cables. This would lead to a significant reduction in the amount of copper needed to transmit electricity. In magnets, superconductors could replace copper coils. This would lead to a significant reduction in the amount of copper needed to create strong magnetic fields. In sensors, superconductors could replace copper wires. This would lead to a significant reduction in the amount of copper needed to detect and measure physical phenomena.

The decline in the demand for copper could have a significant impact on the copper industry. The industry would need to find new markets for copper, or it would need to reduce its production. The decline in the demand for copper would also lead to lower prices for copper, benefit consumers.

Governments must assume a pivotal role in instituting and enforcing stringent regulations on the mining industry. These regulations should encompass comprehensive environmental impact assessments, the widespread adoption of cleaner technologies, and the unequivocal protection of human rights.

Reducing the carbon footprint of the copper industry will be crucial in the coming years, as the world seeks to transition to a low-carbon economy. This could involve the use of renewable energy sources, such as solar or wind power, to power mining and processing activities. It could also involve the adoption of more efficient technologies and processes, such as using recycled copper instead of newly mined copper.

In addition to these efforts to reduce the environmental and social costs of copper mining and production, it is also important to ensure that the benefits of the industry are shared fairly. This could involve working to ensure that workers in the industry are paid fair wages and have safe working conditions. It could also involve working to ensure that local community's benefit from the presence of the industry, through initiatives such as community development projects and revenue sharing agreements.

Copper stands as an undeniable cornerstone of modern technological progress. Yet, beneath its essential veneer, lies a disconcerting reality of environmental and social consequences that demand immediate attention. Proactive measures are indispensable to mitigate these impacts, ensuring equitable distribution of benefits from copper mining while preserving our planet for generations to come. Only through collective action, through the earnest pursuit of cleaner technologies, the exploration of alternative materials, and the implementation of stringent regulations, can we chart a path towards a more environmentally and socially responsible future for copper mining.

The world consumes over 120,000 tons (and rising) of cobalt every year. In terms of the clean energy transition, it is used in the production of metal alloys and in lithium-ion batteries, in which the metal, in the form of lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2), is used as part of the cathode construction. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), approximately 35% of the total cobalt mined per year is used in lithium-ion batteries. This is expected to increase to 50% by 2030, as the demand for electric vehicles (EVs) continues to grow.

However, one country, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) accounts for the majority – around 60% – of global cobalt production. In most cases cobalt is mined in small-scale operations, often by hand, and sold to intermediaries who then sell it to larger companies for processing. This complex supply chain makes it difficult to trace the cobalt back to its source and ensure provenance.

Cobalt mining has major environmental impacts, from the pollution of waterways and land with toxic chemicals to the deforestation of large areas of land, which has and will continue to have significant impacts on local ecosystems and the climate. A 2017 study by the United Nations Environment Programme found that cobalt mining in the DRC has resulted in the contamination of rivers and streams with heavy metals, such as cobalt, copper, and lead. This contamination has had a negative impact on aquatic life and human health. In addition, a 2018 study by the Congolese Institute for Conservation of Nature found that cobalt mining has resulted in the loss of over 1m hectares of forest in the DRC.

The social impacts of cobalt mining in the DRC are equally concerning. Often, these mines are run by small-scale miners who work in dangerous and often hazardous conditions. These workers are paid exceptionally low wages and do not have access to adequate safety equipment or training. Additionally, there have been reports of child labour and other forms of exploitation in the cobalt mining industry in the DRC, which has led to calls for greater transparency and accountability. The profits from the cobalt mining industry in the DRC have been used to fund armed groups and fuel conflict. This has led to instability and insecurity in the region, which has had a negative impact on the lives of people who live and work there.

The DRC government has prohibited child labour in the cobalt mining sector since 2018 and continues to work to improve the working conditions of miners, although its efforts, hampered by corruption scarcity of money and a lack of political will, have been patchy at best. It has failed to engage with local communities most affected by mining, especially in regard to offering a pathway to training and education for those that would otherwise be forced by poverty into mining

There is much to criticize the government of the DRC for with regard to its stewardship of the rare earth metals found within its borders. The large global companies who are the main beneficiaries of the cheap labour of the DRCs young and poor have made efforts to address the power imbalances within their supply chains. For instance Tesla and Apple, have committed to sourcing their cobalt from responsible sources and ensuring that their supply chains are transparent and traceable. Indeed in April 2023 Apple CEO Tim Cook announced Apple’s aim to be using recycled cobalt in 100% of its batteries from 2025.

Additionally, there are initiatives underway to improve the safety and working conditions for miners in the DRC and to promote sustainable mining practices. For instance, the Responsible cobalt Initiative (RCI) is an industry-led initiative from Apple, BMW, Glencore, Samsung, and Tesla that aims to improve the responsible sourcing of cobalt in the DRC. The RCI has developed a set of principles for responsible cobalt sourcing, and collaborates with cobalt producers, buyers, and other stakeholders to implement these principles. In terms of the 3rd sector, The Fair cobalt Alliance (FCA) fronted by NGOs such as Amnesty International, Oxfam, and the Enough Project, has developed a set of standards for responsible cobalt mining, and collaborates with cobalt producers, buyers, and other stakeholders to implement these standards.

Setting standards, either from within the industry and its customers, or from governments and well-meaning NGOs is the easy part. Applying them, gaining adherence to them, measuring and managing that adherence is a different ball game. Here, is where the all too familiar story of well-intentioned soundbites and glossy PR meets the cold light of reality. The processes of both the RCI and the FCA exhibit some inexcusable mistakes. For instance, the RCI does not require its members to conduct a “due diligence” process on its cobalt suppliers thereby leaving the door open for widespread child labour use, while the FCAs focus on traceability is undermined by not requiring its signatories to disclose the companies they are working with. Both of these glaring holes in these bodies’ processes show that the need to maximise margins throughout the supply chain will always outrank any societal or environmental good, even if societal and environmental considerations were the reasons these standards exist in the first place.

Governments, industry and NGOs need to do much more to ensure that the cobalt mining industry in the DRC is sustainable and responsible. This will require greater investment in infrastructure and technology to improve the efficiency and safety of mining operations, as well as greater transparency and accountability throughout the supply chain. Additionally, there needs to be greater support for local communities and workers, including efforts to improve access to education, healthcare, and other basic services.

While cobalt is a critical component in the devices we use every day, the mining of this precious metal has had significant impacts on both the environment and the people who live and work in the DRC. To address these challenges, vastly-improved efforts to promote sustainable and responsible mining practices are needed.

The Guardian, amongst others, are reporting that the UK government is considering dropping its flagship £11.6 billion climate pledge, to reduce the UK's carbon emissions to net zero by 2050. The pledge includes investment in renewable energy, electric vehicles, and energy-efficient buildings. However, there is fear stemming from budget constraints as a result of Brexit the pandemic and war in Ukraine that the pledge might be abandoned. The UK Treasury is reported to have estimated that in order to meet the £11.6bn target by 2026, it would have to spend 83% of the Foreign Office’s official development assistance budget on the international climate fund.

There will be a chorus of protests at this news from climate activists, politicians, climate scientists and climate thought leaders around the world to the very idea of the UK not abiding by its climate funding pledges. We have no hesitation in adding out voice to this chorus.

This is not the first time that the UK government has been accused of cutting back on its green commitments. In 2013, former Prime Minister David Cameron was reported to have said that he wanted to "cut the green crap" from energy bills.

If the UK government is serious about avoiding the worst impacts of climate change, it must prioritize its commitment to decarbonisation. Abandoning its funding pledges will have serious impacts on the country’s ability to meet its #netzero commitments. The UK is already falling short on its progress to meet its 2050 net-zero emissions target. If the 5th largest economy in the world doesn’t meet these targets, and indeed help developing countries also meet theirs we can forget about avoiding the worst effects of climate change we can see happening right now with extreme weather events, such as heat waves, droughts, floods, and storms now a common occurrence. As if to underscore the problem, June 2023 was the hottest June on record in the UK. It is likely that subsequent summer months will also break heat records. We can expect more of these record breaking summers if we continue to ignore the problem. Rolling back on its already far to meagre £11.6bn-backed climate funding pledge would make it more likely that these events will become more frequent and severe, which could have a devastating impact on people and communities.

To cut climate funding would have a serious detrimental impact on the UK’s recovering economy, The UK economy has been battered and bruised firstly, as the rest of the world’s economy has been, by the pandemic which stretched its internal resources and war in Ukraine which cut off supplies and raising fuel prices. These problems have been exacerbated in the UK by Brexit and woeful economic decisions by successive Conservative governments. The Green Economy is a growing sector, with the promise of over 1 million new jobs created by 2030. Again, as with the race to net zero, the UK is already lagging behind its peers. with the US committing $500Bn to its equivalent Inflation Reduction Act, focused on building new climate focused industries. The EU is projecting spend of €578Bn on climate related projects between 2021 and 2027. India has set aside €2.18bn in 2023 alone for developing its climate change related industrial base.

Rolling back on its funding pledges is also huge credibility issue for the UK. From chairing and hosting GOP26, to being one of the first major industrialised countries in the world to enshrine its net zero target in law, been praised for its climate leadership and ambition. Even the threat of reneging on the pledges it has already made to honour its pledges damages this leadership image. Not only does it make the UK look untrustworthy on the global stage, it undermines any influence ethe country can have in encouraging other nations to countries to agree to and meet their obligations.

To say we would be “disappointed” at this news would be an understatement. Surprised? No. We would have much preferred the funding levels to be moving the opposite direction. Whilst being doubled in 2019 from £5.8bn, this spending would be over a 5-year period. We would have rather seen a much more significant sum than £11bn spend on an annual basis.

Lord Goldsmith’s suggested on leaving his governmental role in June 2023 that the UK Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, is simply uninterested in climate change. Right now we would find it very difficult to argue with this suggestion.